Understanding Future Uses of Roofspace and Defining An Early Path to Profitable Roof Estate Investing

June 1st, 2015

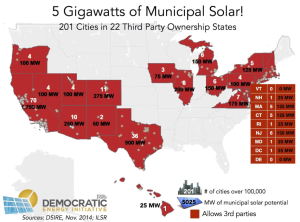

Via the Institute of Local Self Reliance, an interesting report on the public rooftop solar opportunity present in cities around the United States which estimates that mid-sized cities could install as much as 5,000 megawatts of solar—as much as one-quarter of all solar installed in the U.S. to date—on municipal property, with little to no upfront cash.:

In 2012, ILSR published a pair of reports that projected, by 2021,10% of electricity in the U.S. could come from solar and at a lower price—without subsidies—than utility-provided electricity. In 2014 and 2015, Environment America’s Shining Cities reports examined how cities were catalysts for solar development.

However, there has been a missing piece in the examination of how cities can support solar energy: what city leaders have done and can do to use solar on their own buildings.

ILSR estimates that over 5,000 megawatts (MW) of solar could be inexpensively installed almost immediately on municipal property—more than a quarter of the nationwide total solar capacity through September 2014. This includes just the municipal buildings of the approximately 200 cities with 100,000 or greater population. But it requires city officials to overcome a few, surmountable barriers.

The Public Rooftop Solar Opportunity

The opportunity of municipal solar spans financial savings, pollution reductions, and job creation:

Energy Savings: New Bedford, MA, is saving $6 to $7 million per year on electricity through its 16 MW of solar installations on municipal properties, which is 2.5% of the entire city budget.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions: Maximizing New York City’s solar potential with 410 MW of solar would reduce emissions by 1.78 million metric tons, 3.7% of the city’s total emissions.

Significant Economic Impact: Maximizing Kansas City’s municipal solar potential of 70 MW could create 1400 jobs and add $175 million to the local economy.

Overcoming the Economic Barrier with 3rd Parties

The primary incentive for solar is the 30% federal tax credit, a deal that doesn’t apply to local governments. The federal government also provides accelerated depreciation for solar projects, resulting in a tax write-off worth nearly another 30% of a project’s value. The following charts illustrates how the limitations of federal incentives make the economics more challenging for municipally-owned solar.

Although cities face a number of challenges, economic and otherwise, to installing solar, the third party ownership option—if available—ought to trump most of them. For suitable sites that won’t need a near-term roof replacement, third party ownership removes virtually all of the financial barriers to solar, and covers maintenance and operations. While some barriers (like lack of aggregate or virtual net metering) remain, most cities have a substantial solar opportunity.

Barriers

While the most substantial barrier is cost, cities have named several other barriers to reaching their full solar potential:

Physical Limits: city structures may lack sunshine or suitable roof space, for example.

Historic / Aesthetic: some city buildings are historic and may have state or federal limitations on adding solar.

Expertise and Legal Issues: some cities are reluctant to negotiate solar contracts without greater in-house expertise.

Bureaucracy: cities may require multiple levels of approval for a single solar array.

Net Metering: aggregate net metering and virtual net metering substantially increase the maximum possible solar capacity for a city, but these policies apply to just 17 and 11 states, respectively.

However, Public Rooftop Revolution features stories from five cities that have overcome many of these barriers to solar on city property.

The Featured Five Solar Cities

ILSR’s featured five cities provide a fairly comprehensive look at how cities can overcome solar barriers, from cost to bureaucracy:

Lancaster, CA: leveraging an excellent solar resource, Lancaster city leadership has deployed several strategies to produce more solar energy on a daily basis than the entire city consumes.

New Bedford, MA: with favorable state policy, New Bedford is cutting city energy bills and deploying more solar per capita on city property than any other city.

Denver, CO: with plenty of open space at the city-owned airport and quality sunshine, Denver is using innovative financing techniques to ramp up city-owned solar.

Kansas City, MO: in the face of restrictive state policy and modest sunshine, this Midwest town still managed to put solar on 59 city buildings.

Raleigh, NC: even with cheap grid power and limited state policy support, this city has made significant strides in installing solar for municipal use with some innovative financing arrangments.

Spillover Effects of Municipal Solar

Municipal solar installations serve a purpose beyond city energy savings. Their presence on city buildings supports solar development in the private sector in several ways:

Inspiring private sector copycats to also install solar.

Giving valuable experience to local solar companies and driving down costs.

Helping city officials understand and simplify solar installations for residents and businesses.

Improving local policy, such as permitting, making solar simpler and less costly.

Sparking changes to state policy, as when the Dubuque, IA, attempt to install solar on a public works building resulted in a court case allowing third party ownership.

Cities have a unique opportunity to cut costs and emissions, boost the economy, and stimulate their solar market with investments in solar on municipal buildings. What are they waiting for?

Introduction

A revolution is sweeping through the electricity system in the United States, and its name is solar. With costs falling precipitously, millions of electricity customers from Hawaii to Massachusetts are going solar, a dynamic that not only lowers costs and reduces pollution but is birthing a new, democratic energy system. Solar energy decentraliz es power generation, but also breaks apart monopoly control to decentralize the economic benefits of the electricity system.

In 2012, ILSR published a pair of reports that projected, by 2021,10% of electricity in the U.S. could come from solar and at a lower price—without subsidies—than utility-provided electricity. Up to 100 million Americans could become electricity producers and, combined with solar arrays on commercial rooftops, U.S. rooftops could boast over 300 gigawatts of solar.

By focusing on major metropolitan areas, ILSR’s previous studies helped change the focus on solar energy, from utilities and states to cities. In 2013, we added to the solar analysis with City Power Play, a look at eight powerful policies for aligning a city’s interest in energy and the local economy. In 2014, Environment America published the first edition of Shining Cities, showing which cities were leading in solar development within their borders, and the policy and practical tools for accelerating solar in urban areas.Shining Cities is a terrific assessment of how some cities have already started to unlock their solar potential by removing barriers to deployment.

However, there has been a missing piece in the examination of how cities can support solar energy: what city leaders have done and can do to use solar on their own buildings.

Local governments own and operate hundreds of thousands of buildings. The advent of affordable solar energy provides cities a remarkable opportunity to reduce their operating costs, shrink their climate footprint, and boost the local economy.

For example, Kansas City, Missouri (pop. 467,000) has enough suitable rooftop space on municipal buildings to install nearly 70 megawatts (MW) of solar, producing enough energy each year to cut city electric bills by $8.7 million per year. Maximizing use of this rooftop space with solar would also create 1400 construction jobs and add over $170 million to the local economy.

It’s also an environmental opportunity. Kansas City is among 1,000 cities that have signed onto the U.S. Mayor’s Climate Protection Agreement. But ILSR’s earlier research shows that few of these cities have been able to hold to their commitments. The 70 MW of solar possible on Kansas City municipal property could reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions by 15,300 metric tons per year. New Bedford, MA, already has more than 16 MW on public property, Lancaster, CA, has 9 MW.

Cities can also serve as a model for residents and businesses, leading by example and also by rule, using their authority over zoning, permitting, and taxing to make solar more economical. Kansas City has shortened permit waiting times to eight hours or less, provided online permitting, and lowered inspection times to eight hours or less. These efforts help the city rank 2nd in the Midwest in solar per capita, its 11 megawatts resulting in 25 Watts per person. Denver cut its solar permitting fee to just $50, helping to more than double citywide solar deployment from January 1 to December 31, 2014.

Despite the substantial benefits to the public (and private) sector of municipal solar development, few cities have done more than install a few solar panels when state or federal money is available. There are several barriers to municipal solar adoption, including ineligibility for federal tax incentives, competition for scarce operating and capital budgets, poor state policies, and others. ILSR’s research suggests these barriers can be overcome, and if cities took the lessons of New Bedford or Lancaster, they could generate an impressive amount of electricity from solar.

ILSR estimates that over 5,000 MW of solar––more than a quarter of the nationwide total capacity through September 2014––could be installed on the municipal buildings of more than 200 cities with 100,000 or greater population. These cities were selected for their size (and contain 20% of the U.S. population), but also because they inhabit states that allow them to contract with a third party owner to own and operate solar on their own property, and to receive the economic benefits of solar with zero money down. In other words, for suitable building sites in these cities, there are no meaningful barriers to maximizing municipal solar.

This report illustrates the broad municipal solar opportunity, tells the story of five solar cities, and identifies opportunities to overcome the barriers that have slowed solar’s adoption on public property.

The Public Rooftop Solar Opportunity

Solar on municipal buildings provides three direct impacts: energy savings, greenhouse gas emission reductions, and jobs. Unlike many other city expenditures, it also pays back on the city’s bottom line.

Many Megawatts and Energy Savings

Municipal buildings often have flat rooftops that are attractive sites for solar. For example, New York City could have over 400 megawatts (MW) on public buildings (four times more than Mayor de Blasio’s 10-year goal). San Francisco could generate 32 MW of power from school rooftops alone, nearly 10% of the city’s potential for all public and private buildings. Minneapolis, MN, could get 18 MW on public buildings.

Several cities have already captured much of their potential. Lancaster, CA, generates enough solar energy, with 9 MW, to power over half its municipal operations and save approximately $450,000 per year. New Bedford, MA, is saving $6 to $7 million per year on electricity through its 16 MW of solar installations on municipal properties, which is 2.5% of the entire city budget.

Cities can save even more on solar with bulk purchasing. A joint procurement effort in the San Francisco area has 19 agencies issuing a joint request for proposals for 31 megawatts of solar to power 186 facilities. The total cost could be reduced by as much as 45%.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions

If rooftop solar for cities were just a matter of greenhouse gas reductions, then cities would be better off investing in energy efficiency.

Fortunately, energy savings, economic impact, and the many spillover effects into the private sector (discussed later) outweigh the relatively small reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, many cities are able to install solar without any commitment of city dollars, achieving emissions reductions and energy savings simultaneously.

The following table illustrates the greenhouse gas emissions reductions potential of municipal solar for three cities. In Washington, DC, it’s based on a current proposal to install 10 MW of municipal solar; in San Francisco, it’s based on maximizing school rooftop potential (32 MW); in New York it’s based on maximizing public building rooftop potential (410 MW).

Washington, D.C. has 527,000 metric tons of emissions from government operations, 6% of the 8.9 million metric tons from all sources in the District. The city recently put out a request for proposal calling for 10 megawatts (MW) solar on municipal buildings. The 10 MW will produce 12.9 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity per year, displacing 12,300 metric tons of carbon dioxide (2% of the government’s emissions, 0.1% of total city emissions).

San Francisco has 5.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per year (2010). Covering schools with 32 MW of solar would produce 49.7 million kWh of electricity per year, displacing 14,900 metric tons of carbon dioxide (0.28% of city emissions).

New York City has 48 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per year (2013). In the next decade, the addition of another 100 MW of solar on municipal buildings would produce 132 million kWh of electricity and cut emissions by 433,000 metric tons (approximately 1% of the city’s total). Maximizing the city’s solar potential with 410 MW of solar would reduce emissions by 1.78 million metric tons, 3.7% of the city’s total emissions.

Significant Economic Impact

More impressive is the fact that every megawatt of solar results in 20 local construction jobs and $2.5 million dollars added to the local economy. Solar also produces more jobs per megawatt of capacity than most other electricity sources.

Maximizing Kansas City’s municipal solar potential, for example, would create 1400 jobs and add $175 million to the local economy. For Minneapolis, it would create 360 jobs and add $45 million to the city economy.

Solar also reduces imports of fossil fuels for electricity generation. In Minnesota, for example, over $20 billion a year leaves the state for the import of fossil fuels for electricity, transportation, and building heating and cooling.

This entry was posted on Monday, June 1st, 2015 at 6:18 pm and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Educated at Yale University (Bachelor of Arts - History) and Harvard (Master in Public Policy - International Development), Monty Simus has held a lifelong interest in environmental and conservation issues, primarily as they relate to freshwater scarcity, renewable energy, and national park policy. Working from a water-scarce base in Las Vegas with his wife and son, he is the founder of Water Politics, an organization dedicated to the identification and analysis of geopolitical water issues arising from the world’s growing and vast water deficits, and is also a co-founder of SmartMarkets, an eco-preneurial venture that applies web 2.0 technology and online social networking innovations to motivate energy & water conservation. He previously worked for an independent power producer in Central Asia; co-authored an article appearing in the Summer 2010 issue of the Tulane Environmental Law Journal, titled: “The Water Ethic: The Inexorable Birth Of A Certain Alienable Right”; and authored an article appearing in the inaugural issue of Johns Hopkins University's Global Water Magazine in July 2010 titled: “H2Own: The Water Ethic and an Equitable Market for the Exchange of Individual Water Efficiency Credits.”